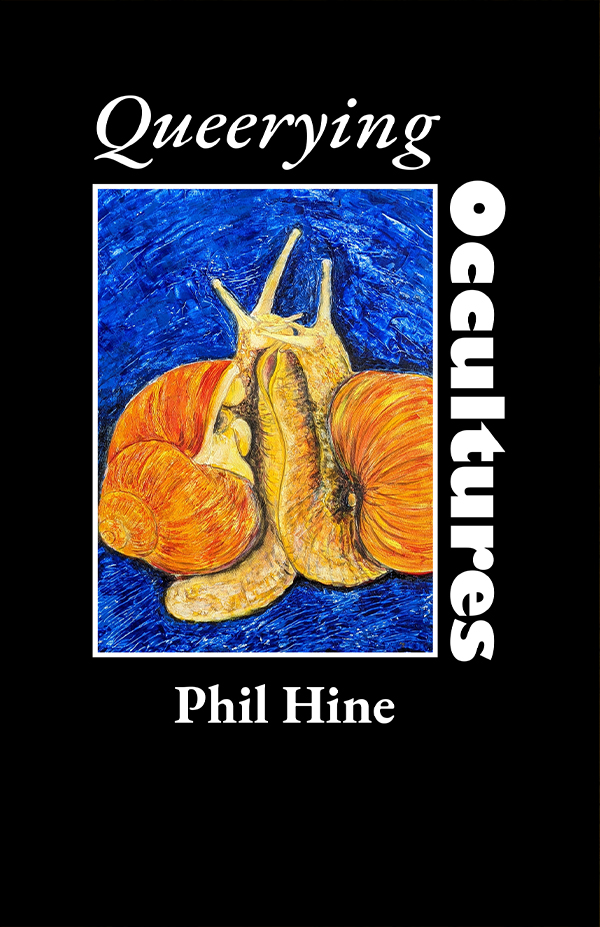

Queerying OcculturesEssays from Enfolding Vol. 1

| Paperback | MOBI eBook For Kindle Devices | ePub eBook For All Other Devices |

|---|---|---|

$19.95 | $9.99 50% savings | $9.99 50% savings |

Product Information

| Format: | Paperback |

|---|---|

| Pages: | 200 pages |

| ISBN-10: | 1-61869-793-5 |

| ISBN-13: | 978-1-61869-793-6 |

Description

What is Queerying Occultures? 'Queerying' is a portmanteau word from 'Queer’ and 'Query'—classic Phil Hine word play. Occulture is another portmanteau word meaning 'Hidden Culture' (from ‘Occult’ and 'Culture').

The occult is Queer. Historically. Intrinsically. Radically. Wonderfully Queer. Yet at times this essential fact can feel unacknowledged in wider Occulture dialogues. Addressing this, Phil Hine’s Queerying Occultures is a collection of queer-themed essays exploring, questioning and reflecting on the diverse trajectories that might arise from applying queer questioning to occultural themes and practices. Drawing on perspectives from Queer Theory, history, Continental Philosophy, and shared experience, Hine explores subjects as diverse as Shamanism and gender-variance; the rise of the Queer Pagan approaches; the uncomfortable history of occult homophobia; Queer perspectives on Tantra, Pan, Sacred Spaces, and Crowley in Boy Bar Berlin. This far-reaching, necessary book is both a celebratory resistance text and indispensable investigation of the Queer in Occulture.

Read an Excerpt

Prologue: Queer and Loathing in Twentieth-Century Occultism

As 2022 speeds to a close, human rights are under attack in myriad ways that seem determined to drag us back to the 1950s, if not further. The USA Supreme Court's overturning of Roe vs. Wade, guaranteeing federal constitutional protections of abortion rights in May; the escalating transphobia in European and the USA's 'culture wars'; the homophobic 'Groomer' narrative being pushed by American and British conservatives. Even the 'Satanic Panic' of the 1980s and 90s is gaining traction once more (although really, it never went away).

Histories—particularly uncomfortable histories—tend to get swept under the carpet. Ignored, all too conveniently forgotten, unspoken. For many years, the queer entanglements of occultism in the global North (particularly in the UK) were sidelined and seemingly of little interest to both scholars and practitioners alike. I can remember talking to a gay (but closeted) occultist in mid-1980s—a well-known author of several books on magic, who told me frankly that I wouldn't get any interest in a book on queer magic. "Occultists don't want to hear about queers, and queers don't want to hear about the occult," was more or less how he put it to me. He went on to tell me that in the 1960s, he'd been a member of an entirely gay ceremonial magic lodge—but that due to his 'oath of initiation' he could not say more. He also told me that if he revealed himself to be a gay magician, then no one would come to his workshops and lectures. This was not an untypical attitude in the British occult scene during the 1980s—doubtless not helped by the responses to the AIDS virus, dubbed "the gay plague" in the media. There were calls to make homosexuality illegal once more, and that AIDS victims should be interned in what was effectively, concentration camps. This was not a good time to be out as 'bi'. Bisexuals were frequently demonized as being 'worse' than Gays, as they threatened 'normal people.' The UK was also under the sway of a Conservative government keen to crack down on 'permissiveness' who, in 1988 passed the infamous Section 28—a series of laws that prohibited local authorities to publish or promote any material that promoted the concept of "homosexuality as a pretended family relationship."

On the UK's Pagan and Occult scene, didactic statements and 'occult laws' demonising anyone not heterosexual, abounded. The selection of quotations which accompany this essay were compiled by myself and Paul McAndrew in 1991. We simply went through the books on our shelves and picked out choice quotes. They show how widespread the condemnation of the non-heterosexual was in that period—Wicca, Thelema, Sacred Sex, Tantra, Ceremonial Magic, Macrobiotics; choose any tradition or spiritually-inclined genre from that time and you'd be bound to find someone making the argument that non-straight folk were beyond the pale. There was much talk of blocked chakras, reverse kundalini, plugs and sockets, and polarity—all favourite justifications for condemnation. Perhaps my 'favourite' is the one that says "homosexuals are not human"—a kind of queered-up Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Some magical orders openly declared they did not accept anyone who was homosexual. The High Priestess of a Wiccan coven I was in told me that anyone who was gay or bisexual could not possibly advance spiritually. People knew of Aleister Crowley's bisexuality, of the passionate homoeroticism of his Hymn to Pan, but that, for some at least, made Crowley all the more suspect. I remember going to a lecture about Crowley's infamous 'Choronzon Working' with Victor Neuburg in 1909. At one point the lecturer mumbled, "And we presume something homosexual took place," whereupon Paul & I, who were sitting in the front row, shouted "What? Tell us?" and the lecturer blushed and hid behind his notes.

This 'occult homophobia' gradually changed over the next two decades or so. More queer folk began to move around on the UK's occult & pagan scenes. They challenged the prevailing unthinking prejudices, often just by being present and refusing to be cowed by blatherings about polarity or blocked chakras. But it was slow going, and for some, a struggle. A trans friend was suddenly barred from going to a goddess circle (I found out, years later, that the person behind the banning was someone I had, up to that point, considered a friend). I heard of a young man who'd come out as gay to the ceremonial magic lodge which had been, up until that moment, the centre of his life. They'd ceremonially 'banished' him, and he later committed suicide. There was a woman friend who stopped going to pagan meetings and conferences because of the constant nudging and whispering about her being a lesbian. I recall visiting a local Wiccan coven in the mid-1990s, where even sharing a semi-formal chalice of wine (passed along with a chaste kiss) involved getting everyone present into a male-female chain. The one gay man in that coven told me proudly that he was 'straight' when he stepped into the circle.

One reason that attitudes changed was the popularity of networking and grass-roots organising. By the mid-1980s, Pagans inspired by Marilyn Ferguson's 1987 book, The Aquarian Conspiracy, and the politically-engaged Witchcraft of Starhawk, were becoming increasingly active. These moves coincided with Pagans and Occultists becoming much more visible to the general public, amid a growing interest in ecological activism, animal rights, and alternative lifestyles. At the same time, many within the Pagan and Occult scene cherished their identification as 'outsiders,' and had little interest in engaging with the wider public.

The rise of interest in Women's Spirituality and activism also helped fuel these changes. In 1989, Gordon "the Toad" McLellan founded HOBLink, a network offering support to LGBT Pagans and Occultists, and for raising awareness of LGBT issues in the wider Pagan/Occult communities. There were HOBLink newsletters and occasional social meetings and workshops. On one occasion, HOBLink was refused the use of room space by the London Gay and Lesbian Centre because HOBLink included 'bisexuals.' In an interview in 1991, Gordon commented on the state of the Pagan scene in regard to LGBT Pagans:

"Some elements of the pagan community are trying to sell it as nice and safe and essentially middle-class and not at all threatening to society. They might well try to stuff us back into our broom cupboards. I think for paganism to try and present itself like that is a betrayal of what we stand for. For me, being pagan means working with the Earth, and if I try and sell myself as a nice, sweet, slightly eccentric person who's not a trouble-maker at all, then I'm betraying the Earth, because this society is destroying the Earth."

British attitudes were also influenced to some degree by developments in North America, such as the rise of queer anthropologies, and a growing interest in the relationship between gender-variance, religion and occultism. A great deal of what was written then can now be criticised, certainly as a universalising tendency to assume that what was queer in 20th-century London, for example, could be retroactively applied to other cultures and the distant past. The notion that all myths or stories reflected modern concerns and sensibilities. But at least they showed that there were hidden histories and stories to uncover.

How did the British parochial attitude towards the place of non-straight people within occult discourse emerge? Where did it come from? We don't have to look far. The UK's occult scene in the 1980s was very different to what it is now. There was a good deal of suspicion among practitioners of different traditions and approaches. Beyond the metropolitan centres (Leeds, London, Oxford), Thelemites and Wiccans (for example) did not tend to mix much. Even owning Crowley's Thoth tarot deck could raise eyebrows and critical comment.

The kind of heterogenous blending of ideas that we see in modern books on Witchcraft, where an author might happily blend elements of Wicca, Chaos Magic, and Thelema into a single narrative, would have been anathema. By the same token, those who felt themselves to be 'proper' Pagans were wary of others pursuing alternative lifeways. I recall from the time I spent co-editing the zine Pagan News, being asked not to publish the site details of an outdoor Pagan gathering because the organisers didn't want 'New Age Travellers' turning up.

Similarly, the attention to history that is so widespread nowadays (thanks to the work of scholars such as Owen Davies, Ronald Hutton and Alex Owen) was not much in evidence. It now seems to me that many of the people I knew back then operated from a predominantly 'mythic' perspective. They had little interest in history beyond the narrative of the burning times, and when they did try to engage with the turbulent events of that decade, they turned to the Arthurian Myths, centering 'Great Britain' as the still vibrant heart of a spiritual world.

The majority discourse on magic was very much couched in terms of binary oppositions. White magic was being 'spiritual.' Focusing on spiritual development while being largely unconcerned with everyday life beyond immediate necessities. Black Magic, on the other hand, was taking drugs, being involved in political activism, questioning occult laws, not having a properly established relationship with 'inner plane adepts'—and, of course, any kind of sexual activity beyond the bounds of heteronormativity. When Chaos Magic began to gain popularity in the late 1980s, the backlash from more 'traditional' mages was palpable. William Gray, for example, in his 1989 book Between Good and Evil: Polarities of Power (Llewellyn Publications) drew a direct comparison between Chaos Magic and AIDS as a spiritual disease, calling Chaos Magic "anarchy" and dismissing it as "Nuclear Nastiness."

Dion Fortune and the Left-Hand Path

The idea that involvement in politics, taking drugs, and not being heterosexual are all indicators of 'Black Magic' (often termed 'the Left-Hand Path') has its roots in the writings of Dion Fortune (1890–1946). A prodigious author in her own lifetime, Fortune's occult fiction and non-fiction have had a tremendous influence on occultism, both in the UK and beyond. After her death in 1946, her flame was kept alive by the Society of Inner Light, and by the late Gareth Knight (1930–2022), the pen name of Basil Wilby, who published several collections of Fortune's essays and books exploring her occult beliefs and practices. Gareth Knight's bald assertion, quoted earlier, draws directly on Fortune's attitudes with his statement that homosexuality is "black magic, perversion and evil."

All of the above indicators of 'black magic' can be found in Fortune's 1930 book, Psychic Self-Defence, still widely regarded as a classic work on self-protection against magical and human adversaries. In Chapter Five, for example, she describes the case of 'D', a youth in his late teens, "one of those degenerate but intellectual and socially presentable types" who has been suffering psychic attacks after visiting a cousin who had been invalided from the front lines during the Great War. The cousin, according to Fortune, had been caught "practising necrophilia" (not an uncommon practice, she says), and furthermore, that "the relations between D and his cousin were of a vicious nature, and one on occasion, he bit the boy on the neck, just under the ear, actually drawing blood." Relations of a 'vicious nature' is a euphemism often associated with depravity and sexual perversity. Chapter Ten, entitled "Non-occult dangers of the Black Lodge" goes further. The 'Black Lodge' is Fortune's term for those occult fraternities engaged in either ordinary or occult criminality (sometimes both). The examples of such lodge activities include: drug trafficking, being "riddled with unnatural vice," being "little more than a house of ill-fame," and being involved with "subversive politics." On the subject of 'unnatural vice' Fortune states that there is "as much danger of corruption in a Black Lodge for boys and youths as there is for women." The police have intervened in such cases, "both here and abroad." This is a dig in the direction of the Theosophical Society, and in particular, Charles Webster Leadbeater. Fortune had joined the Christian Mystic Lodge of the Theosophical Society and became its president, but she left in the wake of the successive Leadbeater scandals.

Fortune may also have been referring to a 1903 homosexual scandal—the so-called Paris Messes Noires ('Black Masses')—organized by the wealthy nobleman and socialite Jacques d'Adelswärd Fersen. These affairs were attended by wealthy friends of Fersen, including some Catholic priests, the main attraction being tableau vivants made of up of naked youths from some of the best schools in Paris. Fersen was charged with "inciting minors to debauchery," and the case was widely publicized. Fersen, who had been imprisoned for five months prior to the trial, was released afterwards, and fined 50 francs. After the trial, Fersen moved to the island of Capri, and in 1905 published Lord Lyllian: Black Masses—a satirical, decadent novel touching on the 1903 scandal and the trial of Oscar Wilde. In her (1929) book Sane Occultism, Fortune alludes to a conspiracy of male occultists who used "homosexual techniques" to build up what she called "dark astral power." In The Esoteric Philosophy of Love and Marriage (1922), Fortune makes her views on sexual perversions quite clear. They are the "solitary stimulation of the generative organs," and "mutual stimulation by two people of the same sex."

Fortune's The Problem of Purity, contains some of her theories on sexual magic as an energetic system, and discusses a practical technique for directing the sex-force to good works of selfless service, rather than dwelling on "the awful consequences its illicit uses may bring in their train."

The Doctrine of Polarity

Another lasting feature of Fortune's work is her doctrine of Polarity, which for Fortune was the key to all magical work. Fortune believed that polarity acted at all levels of existence, from the cosmological to the interpersonal, where in one instance it manifests as sex (although that is not necessarily its most important aspect). Critically—although she accepted the dominant view of the period that as far as the everyday world was concerned, men were naturally active, and women passive—she states that on the inner planes, this polarity was reversed, and that men needed women to supplement and stimulate them, both emotionally and spiritually. This theme is at the centre of Fortune's occult novels such as The Sea Priestess and Moon Magic.

It would be unfair to lay all of the twentieth-century's occult homophobia at Fortune's door, but I think it is fairly obvious that her ideas (together with other circulating notions such as 'reverse kundalini,' blocked chakras, etc., and the near-rigid enforcement of male-female pairings in Wicca) became part of the overall discourse which frowned upon the presence of non-heterosexuals in occult circles, and justified that frowning with occult theories with the status of absolute truths.

Polarity is not merely a theory; it is enacted simultaneously across multiple domains. It can, for example, be expressed spatially—where, for example, during a public ritual, men are asked to gather in one spot and women in another. Gender may be ascribed to particular ritual objects: a knife is 'male,' a cup is 'female,' for example. In Wicca, the act of consecrating wine is often understood as a symbolic act of procreation. In some traditions, there is a strong emphasis on the 'balance' between male and female polarities, that can be expressed as the ratio of male/female members within a group, or the balance of masculine/feminine qualities within a person. Anything that threatens this 'balance' tends to be avoided. When feminist-inspired goddess spirituality began to intersect with more established pagan traditions in the UK, an attitude that was often expressed was that feminists were 'unbalanced' due to their prioritization of women over men.

In 1978 for example, a furor of sorts arose when at speaker at that year's Quest Conference admitted that she would consider admitting homosexuals into her magical group. Shortly afterwards, the following statement appeared in Aquarian Arrow magazine:

"Two members of the [Hornsey] group attended the 'Aquarian Age' symposium held in London on May 13th [1978]. During this meeting it was publicly stated by the leader of one group that she approved of working publicly with homosexuals. The [Hornsey] group wishes to dissociate itself from such a viewpoint.

Further, it considers that any genuinely contacted fraternity could not countenance working with sexual deviants of any sort. The reasons for this should be plain to any properly trained occultist. It is reasonable to conclude, therefore, that of the other 'leaders' and delegates present, there were none who were genuinely contacted on to the Western Mysteries."

Such a hissy fit! The outrage of the authors of the statement is palpable. They condemn an entire event and all those who attended it as not being "genuinely contacted." Meaning that none of those present had established the proper contact with the inner planes 'Masters' who direct all genuine students of the Western Mystery tradition.

Gradually though, there was a shift in these attitudes across the 1980s–90s. British Wiccan authors for example, had to accommodate the increasing popularity of all same-sex covens that were becoming a more prominent feature of U.S. Wicca. Early disapproval gave way to cautious acceptance. Janet and Stewart Farrar, in their A Witches' Bible (1984), noting the existence of single-sex covens, gave their opinion that all-women covens could work, as the "cyclic natures" of their members would provide the required "creative polarity," but they went on to say that, in their opinion, all male-groups would be "a mistake" and that male-only groups would be best sticking to ritual magic, for example, the system of the Golden Dawn.

They go on to remark: "We deliberately refrain from commenting on the 'gay' covens (another particularly American phenomenon), because we feel that we are not equipped to do so, and because anything we could say might be interpreted as anti-homosexual prejudice." After stating that they have homosexual friends and have defended them, they go on to remark, "We have even had one or two homosexual members during our coven's history, when they have been prepared and able to assume the role of their actual gender while in a Wiccan context." To give them their due, the Farrars did, over time, shift their attitudes, and in later books, openly advocated that gay men should be allowed to practice witchcraft.

At least some of the homophobic attitudes within Wicca are widely believed to stem from Gerald Gardner. Doreen Valiente, in her 1989 book, The Rebirth of Witchcraft, remarked that she had been told that homosexuality was "abhorrent to the Goddess," and that the Goddess would curse same-sex practitioners. Valiente says that she believed this, but later came to question it—"Why should people be 'abhorrent to the Goddess' for being bom the way they are?"

Yet at the same time that attitudes were changing, queers were still, by and large, expected to accommodate themselves to the male-female polarity structure to which many covens and magical groups still held fast. Thus, a gay man became 'acceptable' if he was willing to play the role of a (presumably) heterosexual male deity in dynamic tension with a goddess, probably being embodied by a straight woman. The notion that two or more gods or goddesses might want to get it on was still anathema. Further, the idea that a man might want to invoke a goddess upon themselves, or a woman a god, was still thought of as unorthodox or even 'risky' by some groups well into the late 1990s.

A general problem with esoteric theories of sexuality and gender is that they are, all too often as I noted earlier, held to be cosmic truths or universal laws, rather than discourses that have emerged over time and in particular cultures. This is one reason why binary theories of polarity (drawing on electrical analogies or Jungian themes) are so hard for some practitioners to move away from; they are held to be universal principles operating at every level of existence from the personal to the cosmic. Also, works that are considered to be 'classics' of their time (such as Dion Fortune's Psychic Self-Defence) continue to be in circulation, effectively ensuring that the attitudes to sexuality and gender expressed by earlier generations of authors never quite lose their traction or go entirely out of fashion.

Where are we now?

Since the beginning of the new century, there has been a steady stream of books emerging that in one way or another, 'queer' magical practice or open up space for non-heterosexual practitioners who, not that long ago, would not have been even deemed capable of practising occult traditions. Some voices have accommodated to polarity discourse, bending it in the process. Some reject it utterly. These books speak to new generations of practitioners who are more aware of, and critical of the prejudices of what has gone before. The conservatism, casual racism, and universalism are glaringly obvious and are being called out as such. The idea that esoteric practice demands political and ethical commitments is no longer thought to be radical. Existing 'traditions' have been re-oriented, and new ones brought into being. Queer voices are reshaping wider occult discourse in surprising and novel ways. In many ways, we have moved from the margins to the centre. To the heart, if you like. The circle has been 'kinked.'

But the biggest change has been undoubtedly the internet, and the rise of social media. The internet has changed everything. Yes, it has its problems. I am not some rose-tinted net romantic. But the simple fact of being able to connect with another person halfway across the planet is momentous. We find that we are not alone; that communities exist; that we can create and shape communities. We can find strength in diversity, and at the same time honour difference. We can afford to be gentle, and recognise the power of collective anger. We can come together—in all the ways that that implies. It is this sense of community, of shared hope that will, I believe, sustain us in resisting those who would see us banished to the margins again.

Editorial Reviews

Queerying Occulture is thought-provoking, articulate, and delightfully transgressive in a manner that no one other than Mr. Hine could manage, and it belongs on all queer bookshelves.

Mat Auryn bestselling author of Psychic Witch and Mastering Magick

Queerying Occulture invites occultists, Pagans and esotericists of all stripes into a radical inquiry of practice. Using queer theory as the starting place and traversing terrains as varied as Paganism, Tantra, polari, and masked balls, Hine destabilizes boundaries and disrupts the categories and essentialisms that many modern occultists take for granted.

Amy Hale author of Ithell Colquhoun: Genius of the Fern Loved Gully

Phil Hine's Queerying Occulture is a brilliant dive into the tributaries of thought and history that flow into a contemporary understanding of what constitutes queer magic, paganism and religion.

Lou Hart co-founder of Queer Pagan Camp